First-time visitors to Washington, D.C. come with a checklist: visit the White House, the Capitol, and as many museums as they and their kids can survive. And of course, there are the city’s iconic monuments on the National Mall.

But history doesn’t stop rolling just because the nation’s backyard is filling up. There’s still a need to enshrine important moments from our current era. So what will the memorials of the future look like?

Here’s a hint: they may not look much like the marble shrines D.C. is known for.

Four designs were chosen as finalists of the “Memorials for the Future” competition run by the National Park Service (NPS), National Capital Planning Commission (NCPC) and the Van Alen Institute. Announced at an event last week at the National Archives, the designs will be refined over the coming months to begin to establish a framework for how to shape the next generation of monuments and memorials.

“It’s easy to think of Washington as formal, classical, and frankly, old fashioned,” said Bob Vogel, NPS’s National Capital Region director at the event. But the city embraced Pierre L’Enfant’s visionary plan for the city even before the swamp was fully tamed, making it a forward-looking place from its earliest days, Vogel said, and it’s fitting that the Mall is home to memorials that make bold, even controversial statements. “While we’re proud of our traditions we also need to challenge ourselves to think creatively about the future,” Vogel added.

Winnowed down from 89 original entries to 30 semi finalists, many designs employed abstract concepts as their central conceit: environmental degradation, migration, and the emotional and physical impacts of terrorism. And to accomplish one goal of the competition—to add new layers of meaning and context to existing structures and places around the city—many teams also incorporated new media and digital technology into their designs.

“Many of the proposals incorporated new topics into their projects that you don’t see often in a memorial,” says David van der Leer, executive director of Van Alen Institute and the lead juror for the competition.

Competition entrants were asked to envision a concept of monuments that could transcend the usual prescription of “guys on a marble pedestal,” but rather evolve with the community around it. Social issues, like immigration and racism, as well topics connected to climate change were two areas applicants trended towards, van der Leer says. “There were a wide range of projects, some more straightforward and some more abstract, but all with the potential to create flexible memorials in the future.”

Two of the finalists were highly conceptual in nature, and van der Leer says the project partners will be working closely with them over the next several months to refine how the idea would actually be implemented and installed.

“The Im(Migrant): Honoring the Journey,” Radhika Mohan, Sahar Coston-Hardy, Janelle L. Johnson and Michelle Lin-Luse, the traditional memorial is re-imagined as a social monument, in which the city itself becomes a destination to experience the themes of immigration and creating a new home out of the foreign.

And “Voiceover,” a proposal by Anca Trandafirescu, Troy Hillman, Yurong Wu and Amy Catania Kulper, puts forward the idea that revisionism is not a negative concept, but a process necessary for understanding all of history in context. While still highly conceptual, the project aims to “expand the original monuments’ meanings and extend the territory of possible memorial subjects,” possibly with the aid of interactive, chatty, bright pink parrots scattered throughout the city.

By contrast, the other two proposals took a slightly more conventional approach, using physical location to underscore their purpose.

“American Wild” envisions using D.C.’s underground Metro stations as equal-opportunity portals to our national parks. By projecting high definition video of 59 natural parks, accompanied by immersive recordings, onto the subway stations’ ceilings, designers Forbes Lipschitz, Halina Steiner, Shelby Doyle and Justine Holzman aim to expand access to the country’s rich collection of natural resources to a broader segment of the population.

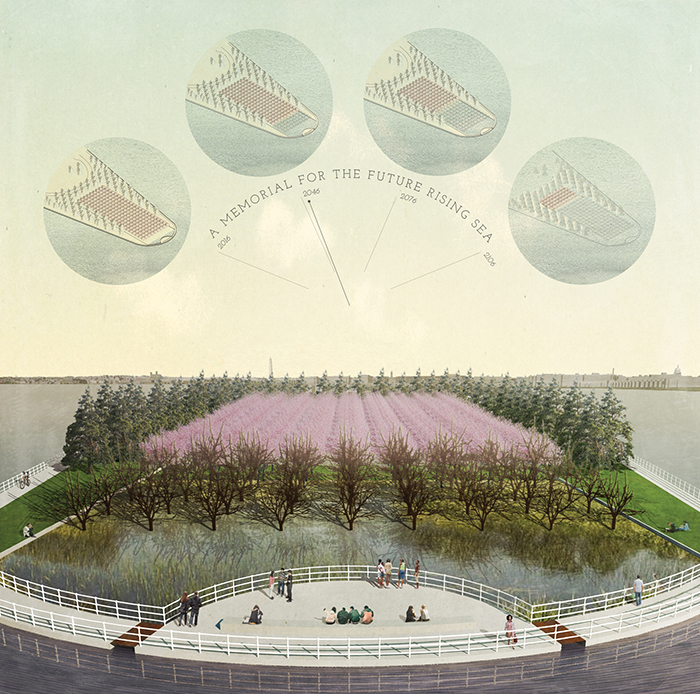

Finally, “Climate Chronograph,” by Erik Jensen and Rebecca Sunter, would transform Hains Point, in East Potomac Park at the confluence of the Anacostia and Potomac Rivers, into a cherry tree grove that is a living demonstration of the impact of climate change. Eventually inundated by the rivers as the planet warms and sea levels rise, the park would serve as “legible demonstration of generational-paced change.”

To advise the design teams as they begin the process of revising and refining their projects, last week’s event included a panel discussion featuring Edward Linenthal, a history professor and scholar of “sacred spaces” at the University of Indiana; Brent Leggs, a preservation specialist with the National Trust for Historic Preservation; and artist Janet Echelman, recognized by Smithsonian magazine in 2014 as an American Ingenuity Award winner.

Changing perspectives both of what a memorial means as well as how it’s viewed and experienced is central to creating meaningful monuments in the future, the three experts agreed.

“One of the ways you begin to deepen identity is to put yourself in someone else’s shoes,” Linenthal said. He used the example of a new approach to visiting Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello: the entire experience changes simply by virtue of the doorway used. “You don’t go in the front door and think about furniture. You go in the kitchen door. Your gaze has changed.”

Leggs agreed, saying that no matter for whom the memorial or monument is intended, the process of creating it should be welcoming and open to people from different walks of life. “Those different perspectives add value to our work,” he said.

Leggs in particular is interested in the power of place—motels, libraries and even ordinary looking homes where historic moments of note unfolded. A new monument need not necessarily be built from scratch when sacred spaces already exist. Founders Library at Howard University, for example, was where much of the legal wrangling for the creation of desegregation laws took place.

“As an iconic building, that place should be celebrated,” Leggs said. “It’s a sacred space not only to civil rights and architecture but as a symbol of education and freedom in America. It is a place we should enjoy, experience and honor.”

And yet, memorials should not preach, or be a definitive answer for questions raised in the viewer’s mind, Echelman said. She used climate change as an example.

“How do you speak to the issues of our climate without being dogmatic?” she asked. “How do you do it in a way that opens a space to think without shutting us down, that is open-ended, that isn’t telling you what to think?”

As to the concept of altering or revising current monuments to reflect current times, Linenthal lamented the idea of “revisionism” being a toxic concept. No other field but history is subject to such criticism, and Linenthal argued that there is value in bringing new questions, materials, research and perspective to existing monuments from the past.

“Any historian who isn’t senile is, by definition, a revisionist,” he said. “You don’t recoil when your doctor doesn’t put leeches on you and say, my god, I’m talking to a medical revisionist! There is no other field except history in which revisionism is looked at in this way.”

The issue of a crowded Mall is unlikely to be resolved, but Echelman suggested that temporary monuments could be one solution. In a time when so much is celebrated en masse via Instagram, Snapchat and other forms of social media, even an ephemeral installation can reverberate long after it’s taken down. Echelman’s piece “1.8,” named for the length of time in microseconds the 2011 Fukushima earthquake in Japan shortened the length of a day on Earth and inspired by wave height datasets from the resulting tsunami, hung above Oxford Circus in London earlier this year for only four days.

“There’s been a lot of afterlife in the sharing of the images and people talking about it from other countries,” Echelman said. “There are other ways ideas are being dispersed.”

Get the latest stories in your inbox every weekday.